Perhaps the most antithetical place on the planet to mention on or around Earth Day is Los Alamos, New Mexico, site of the development of mankind’s ultimate destructive weapon for Planet Earth.

Perhaps the most antithetical place on the planet to mention on or around Earth Day is Los Alamos, New Mexico, site of the development of mankind’s ultimate destructive weapon for Planet Earth.

Yet that’s where I found myself a few days back, fascinated with the Manhattan Project’s beginnings, its secrecy, the lifestyles of its scientists, and the fundamental questions of our ability to let Sleeping Frankensteins lie . . . . or not.

The project began under FDR, whose administration feared Hitler might develop an atomic bomb. The U.S. quickly set in motion a project to develop it first; it found and took  over the site of Ranch School, a boy’s camp in the small mountain town of Los Alamos, New Mexico; displacing dozens of sons of elite American families—families who had paid for their boys to develop character in a ‘rough-rider-style’ school – kind of a preppy pioneer theme.

over the site of Ranch School, a boy’s camp in the small mountain town of Los Alamos, New Mexico; displacing dozens of sons of elite American families—families who had paid for their boys to develop character in a ‘rough-rider-style’ school – kind of a preppy pioneer theme.

pretty utilitarian, right?[/caption]

pretty utilitarian, right?[/caption]

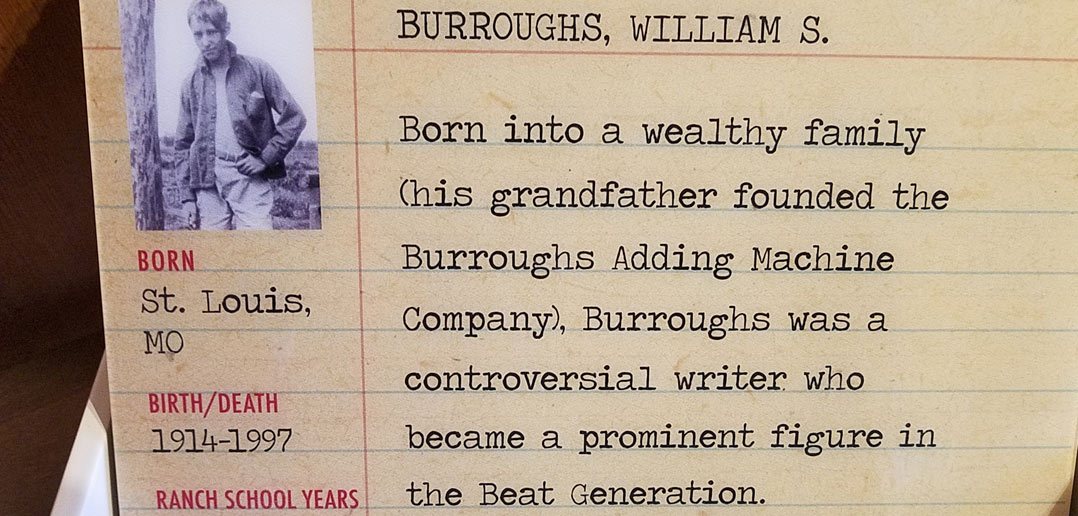

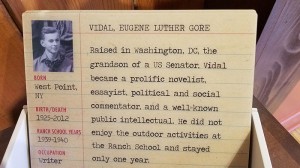

Some of the finest families had sent their teenaged boys there –leafing through the lists I found that future beat writer William Burroughs had attended, as had young Gore Vidal (apparently he hated it and left before the term was over).

In 1942, the boys were moved out of the Fuller Hall buildings, and physicists from around the world moved in – Enrico Fermi, Hans Bethe, Klaus Fuchs, and J. Robert Oppenheimer among them. While the top scientists stayed on or near the main cabins in choice housing (they had bathtubs, hence were housed on ‘bathtub row’), hundreds of incoming scientists and their families were housed in quickly-assembled army barracks, mobile homes, and newly constructed apartment buildings.

The project, of course, was top secret. All Los Alamos employees had their mail censored; they used a Santa Fe address on letters, any kind of identification, and even on birth and

[caption id="attachment_985" align="alignleft" width="300"] Canadian physicist Louis Slotin was 35 when he was exposed to a lethal dose of radiation. He died 9 days later. The small building in which he did experiments is still standing, but closed to the public.[/caption]

Canadian physicist Louis Slotin was 35 when he was exposed to a lethal dose of radiation. He died 9 days later. The small building in which he did experiments is still standing, but closed to the public.[/caption]

death certificates. They lied to friends and family about their jobs, and led insular existences—working, playing, living together for roughly three years. And yes, a couple of scientists died during experiments (many got sick later).

They got the job done. We all know the results of that. In August 1945, two atomic bombs–Fat Man and Little Boy–destroyed two Japanese cities, killing tens of thousands of innocent Japanese citizens, bringing an end to World War II. Changing mankind’s relationship to a living planet in the process.

Unfortunately, much of Los Alamos’ original village is gone (while the technology the scientists created is still here). Will a nation ever use this devastating weapon again? I asked a museum docent, Doug Reilly, who had worked on Los Alamos and Atomic Energy Commission projects for 38 years (now Los Alamos focuses on nuclear deterrence and weapons stewardship), and traveled to more than 20 countries to measure nuclear weapons programs’ capabilities. What he said reminded me of a line from the movie Field of Dreams:

“If you build it, they will come.”